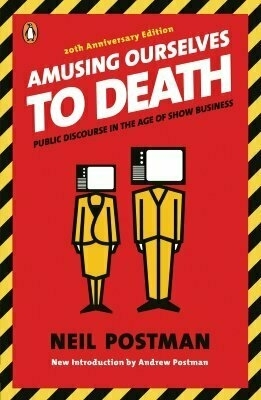

📚 Amusing Ourselves to Death

📚Finished Reading: Amusing Ourselves to Death by Neil Postman

Highly Recommended. I read Technopoly previously and still found a lot of value in this.

My Reading Highlights and Notes

His questions can be asked about all technologies and media. What happens to us when we become infatuated with and then seduced by them? Do they free us or imprison us? Do they improve or degrade democracy? Do they make our leaders more accountable or less so? Our system more transparent or less so? Do they make us better citizens or better consumers? Are the trade-offs worth it? If they’re not worth it, yet we still can’t stop ourselves from embracing the next new thing because that’s just how we’re wired, then what strategies can we devise to maintain control? Dignity? Meaning?

This book is about the possibility that Huxley, not Orwell, was right.

Part I.

1. The Medium Is the Metaphor

Our politics, religion, news, athletics, education and commerce have been transformed into congenial adjuncts of show business, largely without protest or even much popular notice. The result is that we are a people on the verge of amusing ourselves to death.

There is no shortage of critics who have observed and recorded the dissolution of public discourse in America and its conversion into the arts of show business. But most of them, I believe, have barely begun to tell the story of the origin and meaning of this descent into a vast triviality.

We are all, as Huxley says someplace, Great Abbreviators, meaning that none of us has the wit to know the whole truth, the time to tell it if we believed we did, or an audience so gullible as to accept it.

It is an argument that fixes its attention on the forms of human conversation, and postulates that how we are obliged to conduct such conversations will have the strongest possible influence on what ideas we can conveniently express. And what ideas are convenient to express inevitably become the important content of a culture.

For on television, discourse is conducted largely through visual imagery, which is to say that television gives us a conversation in images, not words. The emergence of the image-manager in the political arena and the concomitant decline of the speech writer attest to the fact that television demands a different kind of content from other media. You cannot do political philosophy on television. Its form works against the content.

We attend to fragments of events from all over the world because we have multiple media whose forms are well suited to fragmented conversation.

the clearest way to see through a culture is to attend to its tools for conversation.

People like ourselves who are in the process of converting their culture from word-centered to image-centered might profit by reflecting on this Mosaic injunction.

We know enough about language to understand that variations in the structures of languages will result in variations in what may be called “world view.” How people think about time and space, and about things and processes, will be greatly influenced by the grammatical features of their language.

Each medium, like language itself, makes possible a unique mode of discourse by providing a new orientation for thought, for expression, for sensibility.

person who reads a book or who watches television or who glances at his watch is not usually interested in how his mind is organized and controlled by these events, still less in what idea of the world is suggested by a book, television, or a watch.

In Mumford’s great book Technics and Civilization, he shows how, beginning in the fourteenth century, the clock made us into time-keepers, and then time-savers, and now time-servers. In the process, we have learned irreverence toward the sun and the seasons, for in a world made up of seconds and minutes, the authority of nature is superseded.

Nonetheless, it is clear that phonetic writing created a new conception of knowledge, as well as a new sense of intelligence, of audience and of posterity, all of which Plato recognized at an early stage in the development of texts.

Writing freezes speech and in so doing gives birth to the grammarian, the logician, the rhetorician, the historian, the scientist—all those who must hold language before them so that they can see what it means, where it errs, and where it is leading.

what my book is about is how our own tribe is undergoing a vast and trembling shift from the magic of writing to the magic of electronics.

We are told in school, quite correctly, that a metaphor suggests what a thing is like by comparing it to something else. And by the power of its suggestion, it so fixes a conception in our minds that we cannot imagine the one thing without the other:

in every tool we create, an idea is embedded that goes beyond the function of the thing itself.

Eyeglasses refuted the belief that anatomy is destiny by putting forward the idea that our bodies as well as our minds are improvable.

And our languages are our media. Our media are our metaphors. Our metaphors create the content of our culture.

2. Media as Epistemology

It is my intention in this book to show that a great media-metaphor shift has taken place in America, with the result that the content of much of our public discourse has become dangerous nonsense.

I raise no objection to television’s junk. The best things on television are its junk, and no one and nothing is seriously threatened by it.

we do not measure a culture by its output of undisguised trivialities but by what it claims as significant.

Therein is our problem, for television is at its most trivial and, therefore, most dangerous when its aspirations are high, when it presents itself as a carrier of important cultural conversations.

Whatever the original and limited context of its use may have been, a medium has the power to fly far beyond that context into new and unexpected ones. Because of the way it directs us to organize our minds and integrate our experience of the world, it imposes itself on our consciousness and social institutions in myriad forms. It sometimes has the power to become implicated in our concepts of piety, or goodness, or beauty. And it is always implicated in the ways we define and regulate our ideas of truth.

For in a print-based courtroom, where law books, briefs, citations and other written materials define and organize the method of finding the truth, the oral tradition has lost much of its resonance—but not all of it. Testimony is expected to be given orally, on the assumption that the spoken, not the written, word is a truer reflection of the state of mind of a witness. Indeed, in many courtrooms jurors are not permitted to take notes, nor are they given written copies of the judge’s explanation of the law. Jurors are expected to hear the truth, or its opposite, not to read it. Thus, we may say that there is a clash of resonances in our concept of legal truth.

the written word is, by its nature, addressed to the world, not an individual.

The written word endures, the spoken word disappears; and that is why writing is closer to the truth than speaking.

the concept of truth is intimately linked to the biases of forms of expression. Truth does not, and never has, come unadorned. It must appear in its proper clothing or it is not acknowledged, which is a way of saying that the “truth” is a kind of cultural prejudice. Each culture conceives of it as being most authentically expressed in certain symbolic forms that another culture may regard as trivial or irrelevant.

“Seeing is believing” has always had a preeminent status as an epistemological axiom, but “saying is believing,” “reading is believing,” “counting is believing,” “deducing is believing,” and “feeling is believing” are others that have risen or fallen in importance as cultures have undergone media change.

Since intelligence is primarily defined as one’s capacity to grasp the truth of things, it follows that what a culture means by intelligence is derived from the character of its important forms of communication.

My argument is limited to saying that a major new medium changes the structure of discourse; it does so by encouraging certain uses of the intellect, by favoring certain definitions of intelligence and wisdom, and by demanding a certain kind of content—in a phrase, by creating new forms of truth-telling.

I am arguing that a television-based epistemology pollutes public communication and its surrounding landscape, not that it pollutes everything.

I will try to demonstrate that as typography moves to the periphery of our culture and television takes its place at the center, the seriousness, clarity and, above all, value of public discourse dangerously declines.

3. Typographic America

The Dunkers came close here to formulating a commandment about religious discourse: Thou shalt not write down thy principles, still less print them, lest thou shall be entrapped by them for all time.

the Lyceum Movement had as its purpose the diffusion of knowledge, the promotion of common schools, the creation of libraries and, especially, the establishment of lecture halls.

The influence of the printed word in every arena of public discourse was insistent and powerful not merely because of the quantity of printed matter but because of its monopoly.

4. The Typographic Mind

Is there any audience of Americans today who could endure seven hours of talk? or five? or three? Especially without pictures of any kind?

Whenever language is the principal medium of communication—especially language controlled by the rigors of print—an idea, a fact, a claim is the inevitable result. The idea may be banal, the fact irrelevant, the claim false, but there is no escape from meaning when language is the instrument guiding one’s thought.

As a consequence a language-centered discourse such as was characteristic of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century America tends to be both content-laden and serious, all the more so when it takes its form from print.

A written sentence calls upon its author to say something, upon its reader to know the import of what is said.

The reader must come armed, in a serious state of intellectual readiness. This is not easy because he comes to the text alone. In reading, one’s responses are isolated, one’s intellect thrown back on its own resources. To be confronted by the cold abstractions of printed sentences is to look upon language bare, without the assistance of either beauty or community.

In a print culture, writers make mistakes when they lie, contradict themselves, fail to support their generalizations, try to enforce illogical connections. In a print culture, readers make mistakes when they don’t notice, or even worse, don’t care.

If we may take advertising to be the voice of commerce, then its history tells very clearly that in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries those with products to sell took their customers to be not unlike Daniel Webster: they assumed that potential buyers were literate, rational, analytical.

Indeed, the history of newspaper advertising in America may be considered, all by itself, as a metaphor of the descent of the typographic mind, beginning, as it does, with reason, and ending, as it does, with entertainment.

Public figures were known largely by their written words, for example, not by their looks or even their oratory. It is quite likely that most of the first fifteen presidents of the United States would not have been recognized had they passed the average citizen in the street. This would have been the case as well of the great lawyers, ministers and scientists of that era. To think about those men was to think about what they had written, to judge them by their public positions, their arguments, their knowledge as codified in the printed word. You may get some sense of how we are separated from this kind of consciousness by thinking about any of our recent presidents; or even preachers, lawyers and scientists who are or who have recently been public figures. Think of Richard Nixon or Jimmy Carter or Billy Graham, or even Albert Einstein, and what will come to your mind is an image, a picture of a face, most likely a face on a television screen (in Einstein’s case, a photograph of a face). Of words, almost nothing will come to mind. This is the difference between thinking in a word-centered culture and thinking in an image-centered culture.

For two centuries, America declared its intentions, expressed its ideology, designed its laws, sold its products, created its literature and addressed its deities with black squiggles on white paper.

The name I give to that period of time during which the American mind submitted itself to the sovereignty of the printing press is the Age of Exposition.

Almost all of the characteristics we associate with mature discourse were amplified by typography, which has the strongest possible bias toward exposition: a sophisticated ability to think conceptually, deductively and sequentially; a high valuation of reason and order; an abhorrence of contradiction; a large capacity for detachment and objectivity; and a tolerance for delayed response.

5. The Peek-a-Boo World

Thoreau, as it turned out, was precisely correct. He grasped that the telegraph would create its own definition of discourse; that it would not only permit but insist upon a conversation between Maine and Texas; and that it would require the content of that conversation to be different from what Typographic Man was accustomed to.

telegraphy gave a form of legitimacy to the idea of context-free information; that is, to the idea that the value of information need not be tied to any function it might serve in social and political decision-making and action, but may attach merely to its novelty, interest, and curiosity. The telegraph made information into a commodity, a “thing” that could be bought and sold irrespective of its uses or meaning.

telegraphy made relevance irrelevant. The abundant flow of information had very little or nothing to do with those to whom it was addressed; that is, with any social or intellectual context in which their lives were embedded.

How often does it occur that information provided you on morning radio or television, or in the morning newspaper, causes you to alter your plans for the day, or to take some action you would not otherwise have taken, or provides insight into some problem you are required to solve?

most of our daily news is inert, consisting of information that gives us something to talk about but cannot lead to any meaningful action. This fact is the principal legacy of the telegraph: By generating an abundance of irrelevant information, it dramatically altered what may be called the “information-action ratio.” Tags: definition

You may get a sense of what this means by asking yourself another series of questions: What steps do you plan to take to reduce the conflict in the Middle East? Or the rates of inflation, crime and unemployment? What are your plans for preserving the environment or reducing the risk of nuclear war? What do you plan to do about NATO, OPEC, the CIA, affirmative action, and the monstrous treatment of the Baha’is in Iran? I shall take the liberty of answering for you: You plan to do nothing about them. You may, of course, cast a ballot for someone who claims to have some plans, as well as the power to act. But this you can do only once every two or four years by giving one hour of your time, hardly a satisfying means of expressing the broad range of opinions you hold.

We may say then that the contribution of the telegraph to public discourse was to dignify irrelevance and amplify impotence.

The principal strength of the telegraph was its capacity to move information, not collect it, explain it or analyze it. In this respect, telegraphy was the exact opposite of typography. Books, for example, are an excellent container for the accumulation, quiet scrutiny and organized analysis of information and ideas.

“Knowing” the facts took on a new meaning, for it did not imply that one understood implications, background, or connections.

In a peculiar way, the photograph was the perfect complement to the flood of telegraphic news-from-nowhere that threatened to submerge readers in a sea of facts from unknown places about strangers with unknown faces. For the photograph gave a concrete reality to the strange-sounding datelines, and attached faces to the unknown names. Thus it provided the illusion, at least, that “the news” had a connection to something within one’s sensory experience. It created an apparent context for the “news of the day.” And the “news of the day” created a context for the photograph.

It may be of some interest to note, in this connection, that the crossword puzzle became a popular form of diversion in America at just that point when the telegraph and the photograph had achieved the transformation of news from functional information to decontextualized fact. This coincidence suggests that the new technologies had turned the age-old problem of information on its head: Where people once sought information to manage the real contexts of their lives, now they had to invent contexts in which otherwise useless information might be put to some apparent use. The crossword puzzle is one such pseudo-context; the cocktail party is another; the radio quiz shows of the 1930s and 1940s and the modern television game show are still others; and the ultimate, perhaps, is the wildly successful “Trivial Pursuit.” In one form or another, each of these supplies an answer to the question, “What am I to do with all these disconnected facts?” And in one form or another, the, answer is the same: Why not use them for diversion? for entertainment? to amuse yourself, in a game?

the loss of the sense of the strange is a sign of adjustment, and the extent to which we have adjusted is a measure of the extent to which we have been changed.

I will try to demonstrate by concrete example that television’s way of knowing is uncompromisingly hostile to typography’s way of knowing; that television’s conversations promote incoherence and triviality; that the phrase “serious television” is a contradiction in terms; and that television speaks in only one persistent voice—the voice of entertainment.

Part II.

6. The Age of Show Business

If television is a continuation of anything, it is of a tradition begun by the telegraph and photograph in the mid-nineteenth century, not by the printing press in the fifteenth.

I must begin by making a distinction between a technology and a medium. We might say that a technology is to a medium as the brain is to the mind. Like the brain, a technology is a physical apparatus. Like the mind, a medium is a use to which a physical apparatus is put. A technology becomes a medium as it employs a particular symbolic code, as it finds its place in a particular social setting, as it insinuates itself into economic and political contexts. A technology, in other words, is merely a machine. A medium is the social and intellectual environment a machine creates.

every technology has an inherent bias. It has within its physical form a predisposition toward being used in certain ways and not others.

The average length of a shot on network television is only 3.5 seconds, so that the eye never rests, always has something new to see. Note: surely much shorter since this was written

what I am claiming here is not that television is entertaining but that it has made entertainment itself the natural format for the representation of all experience. Our television set keeps us in constant communion with the world, but it does so with a face whose smiling countenance is unalterable. The problem is not that television presents us with entertaining subject matter but that all subject matter is presented as entertaining, which is another issue altogether.

There is no conspiracy here, no lack of intelligence, only a straightforward recognition that “good television” has little to do with what is “good” about exposition or other forms of verbal communication but everything to do with what the pictorial images look like.

almost all television programs are embedded in music, which helps to tell the audience what emotions are to be called forth.

When a television show is in process, it is very nearly impermissible to say, “Let me think about that” or “I don’t know” or “What do you mean when you say . . . ?” or “From what sources does your information come?” This type of discourse not only slows down the tempo of the show but creates the impression of uncertainty or lack of finish.

Thinking does not play well on television, a fact that television directors discovered long ago. There is not much to see in it. It is, in a phrase, not a performing art.

The single most important fact about television is that people watch it, which is why it is called “television.” And what they watch, and like to watch, are moving pictures—millions of them, of short duration and dynamic variety. It is in the nature of the medium that it must suppress the content of ideas in order to accommodate the requirements of visual interest; that is to say, to accommodate the values of show business.

how television stages the world becomes the model for how the world is properly to be staged. It is not merely that on the television screen entertainment is the metaphor for all discourse. It is that off the screen the same metaphor prevails. As typography once dictated the style of conducting politics, religion, business, education, law and other important social matters, television now takes command.

Post-debate commentary largely avoided any evaluation of the candidates’ ideas, since there were none to evaluate. Instead, the debates were conceived as boxing matches, the relevant question being, Who KO’d whom?

Our priests and presidents, our surgeons and lawyers, our educators and newscasters need worry less about satisfying the demands of their discipline than the demands of good showmanship.

7. “Now . . . This”

“Now . . . this” is commonly used on radio and television newscasts to indicate that what one has just heard or seen has no relevance to what one is about to hear or see, or possibly to anything one is ever likely to hear or see.

Television did not invent the “Now . . . this” world view. As I have tried to show, it is the offspring of the intercourse between telegraphy and photography.

Stated in its simplest form, it is that television provides a new (or, possibly, restores an old) definition of truth: The credibility of the teller is the ultimate test of the truth of a proposition. “Credibility” here does not refer to the past record of the teller for making statements that have survived the rigors of reality-testing. It refers only to the impression of sincerity, authenticity, vulnerability or attractiveness (choose one or more) conveyed by the actor/reporter.

it is quite obvious that TV news has no intention of suggesting that any story has any implications, for that would require viewers to continue to think about it when it is done and therefore obstruct their attending to the next story that waits panting in the wings.

The viewers also know that no matter how grave any fragment of news may appear (for example, on the day I write a Marine Corps general has declared that nuclear war between the United States and Russia is inevitable), it will shortly be followed by a series of commercials that will, in an instant, defuse the import of the news, in fact render it largely banal.

Imagine what you would think of me, and this book, if I were to pause here, tell you that I will return to my discussion in a moment, and then proceed to write a few words in behalf of United Airlines or the Chase Manhattan Bank. You would rightly think that I had no respect for you and, certainly, no respect for the subject. And if I did this not once but several times in each chapter, you would think the whole enterprise unworthy of your attention. Why, then, do we not think a news show similarly unworthy? The reason, I believe, is that whereas we expect books and even other media (such as film) to maintain a consistency of tone and a continuity of content, we have no such expectation of television, and especially television news. We have become so accustomed to its discontinuities that we are no longer struck dumb, as any sane person would be, by a newscaster who having just reported that a nuclear war is inevitable goes on to say that he will be right back after this word from Burger King; who says, in other words, “Now . . . this.”

Disinformation does not mean false information. It means misleading information—misplaced, irrelevant, fragmented or superficial information—information that creates the illusion of knowing something but which in fact leads one away from knowing. In saying this, I do not mean to imply that television news deliberately aims to deprive Americans of a coherent, contextual understanding of their world. I mean to say that when news is packaged as entertainment, that is the inevitable result.

in saying that the television news show entertains but does not inform, I am saying something far more serious than that we are being deprived of authentic information. I am saying we are losing our sense of what it means to be well informed. Ignorance is always correctable. But what shall we do if we take ignorance to be knowledge?

Huxley grasped, as Orwell did not, that it is not necessary to conceal anything from a public insensible to contradiction and narcoticized by technological diversions.

America’s newest and highly successful national newspaper, USA Today, is modeled precisely on the format of television.

In the age of television, the paragraph is becoming the basic unit of news in print media.

the time cannot be far off when awards will be given for the best investigative sentence.

Whereas television taught the magazines that news is nothing but entertainment, the magazines have taught television that nothing but entertainment is news.

8. Shuffle Off to Bethlehem

on television, religion, like everything else, is presented, quite simply and without apology, as an entertainment. Everything that makes religion an historic, profound and sacred human activity is stripped away; there is no ritual, no dogma, no tradition, no theology, and above all, no sense of spiritual transcendence. On these shows, the preacher is tops. God comes out as second banana.

there is always the question, What is lost in the translation?

To come to the point, there are several characteristics of television and its surround that converge to make authentic religious experience impossible. The first has to do with the fact that there is no way to consecrate the space in which a television show is experienced.

The executive director of the National Religious Broadcasters Association sums up what he calls the unwritten law of all television preachers: “You can get your share of the audience only by offering people something they want.”[3] You will note, I am sure, that this is an unusual religious credo. There is no great religious leader—from the Buddha to Moses to Jesus to Mohammed to Luther—who offered people what they want. Only what they need.

what is preached on television is not anything like the Sermon on the Mount. Religious programs are filled with good cheer.

I think it both fair and obvious to say that on television, God is a vague and subordinate character. Though His name is invoked repeatedly, the concreteness and persistence of the image of the preacher carries the clear message that it is he, not He, who must be worshipped. I do not mean to imply that the preacher wishes it to be so; only that the power of a close-up televised face, in color, makes idolatry a continual hazard. Television is, after all, a form of graven imagery far more alluring than a golden calf.

9. Reach Out and Elect Someone

If politics is like show business, then the idea is not to pursue excellence, clarity or honesty but to appear as if you are, which is another matter altogether. And what the other matter is can be expressed in one word: advertising.

One can like or dislike a television commercial, of course. But one cannot refute it. Indeed, we may go this far: The television commercial is not at all about the character of products to be consumed. It is about the character of the consumers of products.

What the advertiser needs to know is not what is right about the product but what is wrong about the buyer. And so, the balance of business expenditures shifts from product research to market research.

The television commercial has oriented business away from making products of value and toward making consumers feel valuable, which means that the business of business has now become pseudo-therapy.

The commercial asks us to believe that all problems are solvable, that they are solvable fast, and that they are solvable fast through the interventions of technology, techniques and chemistry. This is, of course, a preposterous theory about the roots of discontent, and would appear so to anyone hearing or reading it.

television makes impossible the determination of who is better than whom, if we mean by “better” such things as more capable in negotiation, more imaginative in executive skill, more knowledgeable about international affairs, more understanding of the interrelations of economic systems, and so on.

on television the politician does not so much offer the audience an image of himself, as offer himself as an image of the audience.

In the shift from party politics to television politics, the same goal is sought. We are not permitted to know who is best at being President or Governor or Senator, but whose image is best in touching and soothing the deep reaches of our discontent.

Those who would be gods refashion themselves into images the viewers would have them be.

just as the television commercial empties itself of authentic product information so that it can do its psychological work, image politics empties itself of authentic political substance for the same reason.

The Bill of Rights is largely a prescription for preventing government from restricting the flow of information and ideas. But the Founding Fathers did not foresee that tyranny by government might be superseded by another sort of problem altogether, namely, the corporate state, which through television now controls the flow of public discourse in America.

I would venture the opinion that the traditional civil libertarian opposition to the banning of books from school libraries and from school curricula is now largely irrelevant. Such acts of censorship are annoying, of course, and must be opposed. But they are trivial. Even worse, they are distracting, in that they divert civil libertarians from confronting those questions that have to do with the claims of new technologies. To put it plainly, a student’s freedom to read is not seriously injured by someone’s banning a book on Long Island or in Anaheim or anyplace else. But as Gerbner suggests, television clearly does impair the student’s freedom to read, and it does so with innocent hands, so to speak. Television does not ban books, it simply displaces them. The fight against censorship is a nineteenth-century issue which was largely won in the twentieth. Note: of course now banning is back, but mostly symbolic for tv etc

Our Ministry of Culture is Huxleyan, not Orwellian. It does everything possible to encourage us to watch continuously. But what we watch is a medium which presents information in a form that renders it simplistic, nonsubstantive, nonhistorical and noncontextual;

10. Teaching as an Amusing Activity

in doing away with the idea of sequence and continuity in education, television undermines the idea that sequence and continuity have anything to do with thought itself.

11. The Huxleyan Warning

There are two ways by which the spirit of a culture may be shriveled. In the first—the Orwellian—culture becomes a prison. In the second—the Huxleyan—culture becomes a burlesque.

Of course, Orwell was not the first to teach us about the spiritual devastations of tyranny. What is irreplaceable about his work is his insistence that it makes little difference if our wardens are inspired by right- or left-wing ideologies. The gates of the prison are equally impenetrable, surveillance equally rigorous, icon-worship equally pervasive.

In the Huxleyan prophecy, Big Brother does not watch us, by his choice. We watch him, by ours.

An Orwellian world is much easier to recognize, and to oppose, than a Huxleyan.

To be unaware that a technology comes equipped with a program for social change, to maintain that technology is neutral, to make the assumption that technology is always a friend to culture is, at this late hour, stupidity plain and simple.

It is almost equally unrealistic to expect that nontrivial modifications in the availability of media will ever be made.

I am particularly fond of John Lindsay’s suggestion that political commercials be banned from television as we now ban cigarette and liquor commercials.

Television, as I have implied earlier, serves us most usefully when presenting junk-entertainment; it serves us most ill when it co-opts serious modes of discourse—news, politics, science, education, commerce, religion—and turns them into entertainment packages. We would all be better off if television got worse, not better. The A-Team and Cheers are no threat to our public health. 60 Minutes, Eye-Witness News and Sesame Street are.

The problem, in any case, does not reside in what people watch. The problem is in that we watch. The solution must be found in how we watch.

What I suggest here as a solution is what Aldous Huxley suggested, as well. And I can do no better than he. He believed with H. G. Wells that we are in a race between education and disaster, and he wrote continuously about the necessity of our understanding the politics and epistemology of media. For in the end, he was trying to tell us that what afflicted the people in Brave New World was not that they were laughing instead of thinking, but that they did not know what they were laughing about and why they had stopped thinking.